§2.11 Remainder Terms; Stokes Phenomenon

Contents

- §2.11(i) Numerical Use of Asymptotic Expansions

- §2.11(ii) Connection Formulas

- §2.11(iii) Exponentially-Improved Expansions

- §2.11(iv) Stokes Phenomenon

- §2.11(v) Exponentially-Improved Expansions (continued)

- §2.11(vi) Direct Numerical Transformations

§2.11(i) Numerical Use of Asymptotic Expansions

When a rigorous bound or reliable estimate for the remainder term is unavailable, it is unsafe to judge the accuracy of an asymptotic expansion merely from the numerical rate of decrease of the terms at the point of truncation. Even when the series converges this is unwise: the tail needs to be majorized rigorously before the result can be guaranteed. For divergent expansions the situation is even more difficult. First, it is impossible to bound the tail by majorizing its terms. Secondly, the asymptotic series represents an infinite class of functions, and the remainder depends on which member we have in mind.

As an example consider

| 2.11.1 | |||

with a large integer. By integration by parts (§2.3(i))

| 2.11.2 | |||

| , | |||

with

| 2.11.3 | ||||

On rounding to 5D, we have , , . Taking in (2.11.2), the first three terms give us the approximation

| 2.11.4 | |||

But this answer is incorrect: to 7D . The error term is, in fact, approximately 700 times the last term obtained in (2.11.4). The explanation is that (2.11.2) is a more accurate expansion for the function than it is for ; see Olver (1997b, pp. 76–78).

In order to guard against this kind of error remaining undetected, the wanted function may need to be computed by another method (preferably nonasymptotic) for the smallest value of the (large) asymptotic variable that is intended to be used. If the results agree within significant figures, then it is likely—but not certain—that the truncated asymptotic series will yield at least correct significant figures for larger values of . For further discussion see Bosley (1996).

In both the modulus and phase of the asymptotic variable need to be taken into account. Suppose an asymptotic expansion holds as in any closed sector within , say, but not in . Then numerical accuracy will disintegrate as the boundary rays , are approached. In consequence, practical application needs to be confined to a sector well within the sector of validity, and independent evaluations carried out on the boundaries for the smallest value of intended to be used. The choice of and is facilitated by a knowledge of the relevant Stokes lines; see §2.11(iv) below.

However, regardless whether we can bound the remainder, the accuracy achievable by direct numerical summation of a divergent asymptotic series is always limited. The rest of this section is devoted to general methods for increasing this accuracy.

§2.11(ii) Connection Formulas

From §8.19(i) the generalized exponential integral is given by

| 2.11.5 | |||

when and , and by analytic continuation for other values of and . Application of Watson’s lemma (§2.4(i)) yields

| 2.11.6 | |||

when is fixed and in any closed sector within . As noted in §2.11(i), poor accuracy is yielded by this expansion as approaches or . However, on combining (2.11.6) with the connection formula (8.19.18), with , we derive

| 2.11.7 | |||

valid as in any closed sector within ; compare (8.20.3). Since the ray is well away from the new boundaries, the compound expansion (2.11.7) yields much more accurate results when . In effect, (2.11.7) “corrects” (2.11.6) by introducing a term that is relatively exponentially small in the neighborhood of , is increasingly significant as passes from to , and becomes the dominant contribution after passes . See also §2.11(iv).

§2.11(iii) Exponentially-Improved Expansions

The procedure followed in §2.11(ii) enabled to be computed with as much accuracy in the sector as the original expansion (2.11.6) in . We now increase substantially the accuracy of (2.11.6) in by re-expanding the remainder term.

Optimum truncation in (2.11.6) takes place at , with , approximately. Thus

| 2.11.8 | |||

where , and is bounded as . From (2.11.5) and the identity

| 2.11.9 | |||

| , | |||

we have

| 2.11.10 | |||

where

| 2.11.11 | |||

With given by (2.11.8), we have

| 2.11.12 | |||

For large the integrand has a saddle point at . Following §2.4(iv), we rotate the integration path through an angle , which is valid by analytic continuation when . Then by application of Laplace’s method (§§2.4(iii) and 2.4(iv)), we have

| 2.11.13 | |||

| , | |||

uniformly when () and is bounded. The coefficients are rational functions of and , for example, , and

| 2.11.14 | |||

Owing to the factor , that is, in (2.11.13), is uniformly exponentially small compared with . For this reason the expansion of in supplied by (2.11.8), (2.11.10), and (2.11.13) is said to be exponentially improved.

If we permit the use of nonelementary functions as approximants, then even more powerful re-expansions become available. One is uniformly valid for with bounded , and achieves uniform exponential improvement throughout :

| 2.11.15 | |||

Here is the complementary error function (§7.2(i)), and

| 2.11.16 | |||

the branch being continuous with as . Also,

| 2.11.17 | |||

with as in (2.11.13), (2.11.14). In particular,

| 2.11.18 | |||

For the sector the conjugate result applies.

§2.11(iv) Stokes Phenomenon

Two different asymptotic expansions in terms of elementary functions, (2.11.6) and (2.11.7), are available for the generalized exponential integral in the sector . That the change in their forms is discontinuous, even though the function being approximated is analytic, is an example of the Stokes phenomenon. Where should the change-over take place? Can it be accomplished smoothly?

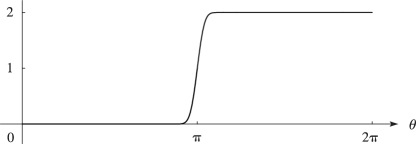

Satisfactory answers to these questions were found by Berry (1989); see also the survey by Paris and Wood (1995). These answers are linked to the terms involving the complementary error function in the more powerful expansions typified by the combination of (2.11.10) and (2.11.15). Thus if (), then lies in the right half-plane. Hence from §7.12(i) is of the same exponentially-small order of magnitude as the contribution from the other terms in (2.11.15) when is large. On the other hand, when , is in the left half-plane and differs from 2 by an exponentially-small quantity. In the transition through , changes very rapidly, but smoothly, from one form to the other; compare the graph of its modulus in Figure 2.11.1 in the case .

In particular, on the ray greatest accuracy is achieved by (a) taking the average of the expansions (2.11.6) and (2.11.7), followed by (b) taking account of the exponentially-small contributions arising from the terms involving in (2.11.15).

Rays (or curves) on which one contribution in a compound asymptotic expansion achieves maximum dominance over another are called Stokes lines ( in the present example). As these lines are crossed exponentially-small contributions, such as that in (2.11.7), are “switched on” smoothly, in the manner of the graph in Figure 2.11.1.

§2.11(v) Exponentially-Improved Expansions (continued)

Expansions similar to (2.11.15) can be constructed for many other special functions. However, to enjoy the resurgence property (§2.7(ii)) we often seek instead expansions in terms of the -functions introduced in §2.11(iii), leaving the connection of the error-function type behavior as an implicit consequence of this property of the -functions. In this context the -functions are called terminants, a name introduced by Dingle (1973).

For illustration, we give re-expansions of the remainder terms in the expansions (2.7.8) arising in differential-equation theory. For notational convenience assume that the original differential equation (2.7.1) is normalized so that . (This means that, if necessary, is replaced by .) From (2.7.12), (2.7.13) it is then seen that the optimum number of terms, , in (2.7.14) is approximately . We set

| 2.11.19 | |||

| , | |||

and expand

uniformly with respect to in each case.

The relevant Stokes lines are for , and for . In addition to achieving uniform exponential improvement, particularly in for , and for , the re-expansions (2.11.20), (2.11.21) are resurgent.

For further details see Olde Daalhuis and Olver (1994). For error bounds see Dunster (1996c). For other examples see Boyd (1990b), Paris (1992a, b), and Wong and Zhao (2002b).

Often the process of re-expansion can be repeated any number of times. In this way we arrive at hyperasymptotic expansions. For integrals, see Berry and Howls (1991), Howls (1992), and Paris and Kaminski (2001, Chapter 6). For second-order differential equations, see Olde Daalhuis and Olver (1995a), Olde Daalhuis (1995, 1996), and Murphy and Wood (1997).

§2.11(vi) Direct Numerical Transformations

The transformations in §3.9 for summing slowly convergent series can also be very effective when applied to divergent asymptotic series.

A simple example is provided by Euler’s transformation (§3.9(ii)) applied to the asymptotic expansion for the exponential integral (§6.12(i)):

| 2.11.24 | |||

| . | |||

Taking and rounding to 5D, we obtain

| 2.11.25 | |||

The numerically smallest terms are the 5th and 6th. Truncation after 5 terms yields 0.17408, compared with the correct value

| 2.11.26 | |||

We now compute the forward differences , , of the moduli of the rounded values of the first 6 neglected terms:

| 2.11.27 | , | |||

| , | ||||

| , | ||||

| , | ||||

| , | ||||

| . | ||||

Multiplying these differences by and summing, we obtain

| 2.11.28 | |||

Subtraction of this result from the sum of the first 5 terms in (2.11.25) yields 0.17045, which is much closer to the true value.

The process just used is equivalent to re-expanding the remainder term of the original asymptotic series (2.11.24) in powers of and truncating the new series optimally. Further improvements in accuracy can be realized by making a second application of the Euler transformation; see Olver (1997b, pp. 540–543).

Similar improvements are achievable by Aitken’s -process, Wynn’s -algorithm, and other acceleration transformations. For a comprehensive survey see Weniger (1989).

The following example, based on Weniger (1996), illustrates their power.

For large , with (), the Whittaker function of the second kind has the asymptotic expansion (§13.19)

| 2.11.29 | |||

in which

| 2.11.30 | |||

With , , , the values of to 8D are supplied in the second column of Table 2.11.1.

| 0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | |||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | |||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | |||

| 8 | |||

| 9 | |||

| 10 |

The next column lists the partial sums . Optimum truncation occurs just prior to the numerically smallest term, that is, at . Comparison with the true value

| 2.11.31 | |||

shows that this direct estimate is correct to almost 3D.

The fourth column of Table 2.11.1 gives the results of applying the following variant of Levin’s transformation:

| 2.11.32 | |||

By we already have 8 correct decimals. Furthermore, on proceeding to higher values of with higher precision, much more accuracy is achievable. For example, using double precision is found to agree with (2.11.31) to 13D.

However, direct numerical transformations need to be used with care. Their extrapolation is based on assumed forms of remainder terms that may not always be appropriate for asymptotic expansions. For example, extrapolated values may converge to an accurate value on one side of a Stokes line (§2.11(iv)), and converge to a quite inaccurate value on the other.